Two pieces in the LA Times today demonstrate why conservatives are increasingly losing the healthcare argument. First up is Michael Tanner of Cato, a guy who's practically an op-ed machine on the subject of healthcare, and right up front he says this about healthcare in America: "It costs too much. Too many people lack health insurance. And quality can be uneven." And he admits that "supporters of the free market" — like him — "have been remiss in positing viable alternatives."

A promising start! But his solution is bizarre:

There are two key components to any free-market healthcare reform. First, we need to move away from a system dominated by employer-provided health insurance....Changing from employer-provided to individually purchased insurance requires changing the tax treatment of health insurance....For tax purposes, employer-provided insurance should be treated as taxable income.

....The other part of effective healthcare reform involves increasing competition among both insurers and health providers. Current regulations establish monopolies and cartels in both industries.

These may or may not be good ideas. They might or might not reduce the cost of healthcare. That much is at least debatable. But they'd do nothing to reduce the number of people who lack health insurance. Just the opposite, in fact. If we took his advice, employers would drop health insurance like hot coals and it's a dead certainty that anybody who's over the age of 50 or has a previous history of anything at all would be unable to get replacement coverage in the individual market. This isn't debatable at all. So why does Tanner think any ordinary middle-aged, middle-class op-ed reader is going to support a plan that increases the odds that they'll have no health insurance in the future? That doesn't make much sense.

But at least Tanner isn't crazy. Unpersuasive, maybe, but not crazy. Charlotte Allen, conversely, thinks that in order to free up some much needed healthcare cash, Barack Obama wants to take all our old people and set them adrift on ice floes to die. Do you think I'm engaged in some bloggy exaggeration for rhetorical effect? Let's roll the tape:

The Eskimos used to set their elderly and sickly adrift on the ice or otherwise abandon them during times of scarcity, and that, metaphorically speaking, is what Obama would like us all to start doing.

....The scarcity of resources to pay for expensive medical procedures will only increase under a plan to extend medical benefits at federal expense to the 47 million Americans who lack health insurance. So why not save billions of dollars by killing off our own unproductive oldsters and terminal patients, or — since we aren't likely to do that outright in this, the 21st century — why not simply ensure that they die faster by denying them costly medical care?

The rest of the piece is a weird Soylent Greenish hodgepodge of scaremongering about comparative effectiveness research, fear of jackbooted government bureaucrats pulling the plug on grandma, and a revival of zombie "No Exit" agitprop last seen in 1994. Allen barely even pretends there's any real evidence for this stuff — mainly because there isn't any, I suppose — so instead she just riffs hysterically about what Obama "seems" to believe about how to reform healthcare. Most weirdly of all, though, at the end of the piece the conservative Charlotte Allen herself seems to suggest that Medicare should be funded with infinite amounts of money and there should never be any restriction on how it's spent. Either that or she doesn't realize that Medicare is the way most old people in America get medical care. Or that Medicare is a government program. Or something. I can't really make sense out of it.

Better conservatives, please. These two are hopeless.

- Related point, Krugman says: Bruce Bartlett misstates the problem

He says:

The problem is that the Obama administration was much too optimistic about how quickly stimulus spending would affect the economy. Christina Romer, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, and Jared Bernstein, chief economist to vice president Joe Biden, forecast in January that the stimulus would reduce unemployment almost immediately.

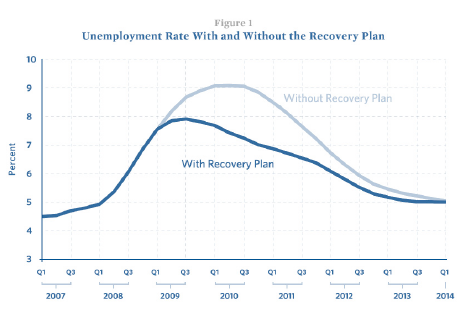

Um, that’s totally false. Did Bartlett even look at the Bernstein-Romer paper? Here’s the key graph:

The predicted impact from the stimulus is indicated by the difference between these two curves. We’re now at the very beginning of 2009Q3; they predicted that the unemployment rate right now would be only a fraction of a percent lower now than it would otherwise be. The impact wasn’t supposed to be really noticeable until late this year, and wasn’t supposed to peak until late 2010.

The problem, in other words, is not that the stimulus is working more slowly than expected; it was never expected to do very much this soon. The problem, instead, is that the hole the stimulus needs to fill is much bigger than predicted. That — coupled with the fact that yes, stimulus takes time to work — is the reason for a second round, ASAP.

Krugman: HELP Is on the Way

The Congressional Budget Office has looked at the future of American health insurance, and it works.

A few weeks ago there was a furor when the budget office “scored” two incomplete Senate health reform proposals — that is, estimated their costs and likely impacts over the next 10 years. One proposal came in more expensive than expected; the other didn’t cover enough people. Health reform, it seemed, was in trouble.

But last week the budget office scored the full proposed legislation from the Senate committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP). And the news — which got far less play in the media than the downbeat earlier analysis — was very, very good. Yes, we can reform health care.

Let me start by pointing out something serious health economists have known all along: on general principles, universal health insurance should be eminently affordable.

After all, every other advanced country offers universal coverage, while spending much less on health care than we do. For example, the French health care system covers everyone, offers excellent care and costs barely more than half as much per person as our system.

And even if we didn’t have this international evidence to reassure us, a look at the U.S. numbers makes it clear that insuring the uninsured shouldn’t cost all that much, for two reasons.

First, the uninsured are disproportionately young adults, whose medical costs tend to be relatively low. The big spending is mainly on the elderly, who are already covered by Medicare.

Second, even now the uninsured receive a considerable (though inadequate) amount of “uncompensated” care, whose costs are passed on to the rest of the population. So the net cost of giving the uninsured explicit coverage is substantially less than it might seem.

Putting these observations together, what sounds at first like a daunting prospect — extending coverage to most or all of the 45 million people in America without health insurance — should, in the end, add only a few percent to our overall national health bill. And that’s exactly what the budget office found when scoring the HELP proposal.

Now, about those specifics: The HELP plan achieves near-universal coverage through a combination of regulation and subsidies. Insurance companies would be required to offer the same coverage to everyone, regardless of medical history; on the other side, everyone except the poor and near-poor would be obliged to buy insurance, with the aid of subsidies that would limit premiums as a share of income.

Employers would also have to chip in, with all firms employing more than 25 people required to offer their workers insurance or pay a penalty. By the way, the absence of such an “employer mandate” was the big problem with the earlier, incomplete version of the plan.

And those who prefer not to buy insurance from the private sector would be able to choose a public plan instead. This would, among other things, bring some real competition to the health insurance market, which is currently a collection of local monopolies and cartels.

The budget office says that all this would cost $597 billion over the next decade. But that doesn’t include the cost of insuring the poor and near-poor, whom HELP suggests covering via an expansion of Medicaid (which is outside the committee’s jurisdiction). Add in the cost of this expansion, and we’re probably looking at between $1 trillion and $1.3 trillion.

There are a number of ways to look at this number, but maybe the best is to point out that it’s less than 4 percent of the $33 trillion the U.S. government predicts we’ll spend on health care over the next decade. And that in turn means that much of the expense can be offset with straightforward cost-saving measures, like ending Medicare overpayments to private health insurers and reining in spending on medical procedures with no demonstrated health benefits.

So fundamental health reform — reform that would eliminate the insecurity about health coverage that looms so large for many Americans — is now within reach. The “centrist” senators, most of them Democrats, who have been holding up reform can no longer claim either that universal coverage is unaffordable or that it won’t work.

The only question now is whether a combination of persuasion from President Obama, pressure from health reform activists and, one hopes, senators’ own consciences will get the centrists on board — or at least get them to vote for cloture, so that diehard opponents of reform can’t block it with a filibuster.

This is a historic opportunity — arguably the best opportunity since 1947, when the A.M.A. killed Harry Truman’s health-care dreams. We’re right on the cusp. All it takes is a few more senators, and HELP will be on the way.

- Benen: SCHUMER PREDICTS PUBLIC OPTION...

Sen. Chuck Schumer (D) of New York has been doing a lot of valuable heavy lifting on health care this year, and yesterday, he went so far as to offer something of a guarantee about a key provision in the reform debate.

"Make no mistake about it, the president is for [a public option] strongly. There will be a public option in the final bill," Schumer said on CBS News's "Face the Nation."

Schumer made his prediction just days before the Senate returned to the work of getting a bill passed by the first week of August amid significant disagreement between Democrats and Republicans -- and among Democrats themselves -- over controversial issues such as the public option.

He added, "We want it to be a fair level playing field, but you need something to keep the big boys honest. And the only thing that really is out there is a public option. We don't trust the private insurance companies left to their own devices, and neither do the American people."

Schumer also said the public plan is all the more likely given President Obama's support, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee's support, and the commitment on the part of House lawmakers.

That last point was bolstered by House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer's (D-Md.) remarks on Fox News: "We think there's going to be a public option. Yes, we think we need that. We need to make sure that there is an option available for public that can't get through at the private insurance. We think that's essential if you're going to have access."

For his part, House Minority Leader John Boehner (R-Ohio) said House Republicans are open to health care discussions, just so long as the majority party agrees from the outset that the reform plan has no public option, no employer mandate, no individual mandate, and no tax increases.

And House Republicans wonder why they're not invited to more policy discussions.

No comments:

Post a Comment